Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law provides a limitation of the exclusive rights of copyright in Fair Use. The Four Factors set forth in the law to be used in a determination of fair use are as follows:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a

commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted

work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted

work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if

such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

It is helpful to develop a standard practice of applying these four factors as you consider copying, distributing, or displaying copyrighted works.

In cases where you plan to share content from journals Murphy Library provides through its electronic databases, providing links is generally more appropriate than copying and distributing entire works.

To assist with your application of the four factors, please use the "Fair Use Checklist" created by Kenneth Crews (Columbia University) and Dwayne K. Buttler (University of Louisville), and found on the website of the Columbia University Libraries/Information Services Copyright Advisory Office. For further information on the checklist and fair use, please also see Kenneth Crews' "A Fresh Look at the Fair Use Checklist," also available from the CU CAO. Both of these items are available for distribution under the Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States License.

Another tool you may find useful is the Fair Use Evaluator available from the American Library Association. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

The University of Minnesota Libraries provides another useful tool: Thinking Through Fair Use Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0)

Here is a sample of language to include with copyrighted material:

NOTICE: The materials provided in this course (or Canvas module) may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. Code). You may print a copy of course materials for your personal study, reading, or research. Reproducing, distributing, modifying and/or making derivative works based on the materials posted here for any other purposes may be an infringement of the owner's copyright.

The Visual Resources Association's information on Intellectual Property Rights and Copyright: Resources on Academic Use of Images: http://vraweb.org/resources/ipr-and-copyright/

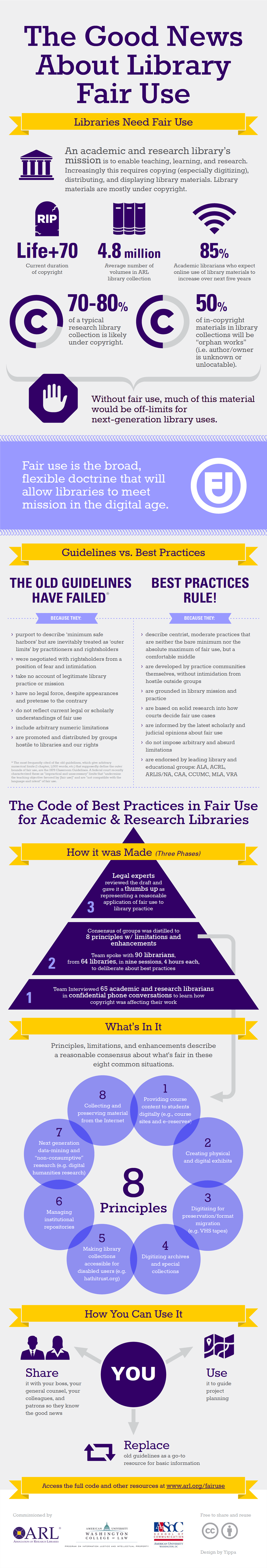

The Association of Research Libraries and its partners, American University's Center for Social Media and Washington College of Law, have recently published a "Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries."

While this code is not a legal document, established community practice may be a consideration in a court of law. Therefore, it is beneficial to the educational community, in the application of our fair use rights, to develop and share "consensus-based community standards relating to commonly experienced conflicts between library practice and perceived copyright constraints." Here is a PDF version: http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/code-of-best-practices-fair-use.pdf

Here is an infographic from ARL titled, "The Good News about Fair Use": https://www.arl.org/resources/the-good-news-about-library-fair-use-infographic/

Unless otherwise noted, ARL web resources are subject to a Creative Commons CC-BY license.

There are all sorts of ideas, theories, guidelines, and rules floating around about Fair Use. Perhaps you've heard a few of these:

(THESE ARE MYTHS AND ARE INACCURATE.)

While the "rules" stated above are useful to consider as we think about Fair Use, none of these exist as part of copyright law (See Crews, Kenneth D. "The Law of Fair Use and the Illusion of Fair-use Guidelines" 62 Ohio St. LJ 599, 2001). The Georgia State case (Case 1:08-cv-01425-ODE USDC Atlanta, decision filed May 11, 2012) may have an impact on future Fair Use practices, but the extent of the impact remains to be seen. (ARL web resources are, unless otherwise indicated, protected by a Creative Commons CC-BY license.)

The "Classroom Guidelines" and other such documents are merely guidelines that this or that organization has come up with and has publicized for various reasons, depending on that organization's stake in manipulating your understanding of Fair Use and copyright infringement.

Fair Use, which was codified in the Constitution of the United States in 1976, has been interpreted in case law to be much more flexible and is applied on a case-by-case basis. This brings us to another important point . . .

Fair Use is not something you can precisely determine on your own, nor is it something your librarian can determine for you. Fair Use is determined in a court of law. In other words, we can work together to apply the four factors of fair use in good faith, but ultimately, the decision would be made by a judge on a case-by-case (that is, work-by-work) basis.

So, the most ethical thing to do is to develop a practice of applying the Four Factors of Fair Use when you are considering copying and distributing copyrighted works.

Please see Brandon Butler. “Urban Copyright Legends.” Research Library Issues: A Bimonthly Report from ARL, CNI, and SPARC, no. 270 (June 2010): 16-20.http://publications.arl.org/rli270/17#. © Association of Research Libraries. Shared with permission.

The difference between “fair use” and “infringement” of a copyright-protected work is not easy to determine. The burden of establishing a “fair use” is on the user and requires a very circumstance-specific analysis of the intended use or reuse of a work. Here are three examples that illustrate this challenge:

|

Weight of Evidence Favors Fair Use |

Gray Area – Opinions May Vary |

Weight of Evidence Does Not Favor Fair Use |

|

Scanning three pages of a 120 page book and posting it to Canvas for one semester. |

Scanning seven pages of a 120 page book and posting it to Canvas for one semester. |

Scanning an entire book and posting it to Canvas. |

|

If the scanned pages are not the “core” of the work in question, a favorable argument for “fair use” exists. |

The amount exceeds established standards for acceptable amounts by one page (i.e. greater than 5%). However, courts are not bound by established standards and the Copyright Act contains no such standards. Opinions will vary. |

Scanning an entire book clearly weighs against a finding of “fair use” as the entire work is used. |

"Professor Eric Faden of Bucknell University provides this humorous, yet informative, review of copyright principle."