Using children’s, teen and young adult books to address difficult themes

Since the mid-18th century when the broad genre “children’s literature” was introduced, children, teen and young adult readers have traditionally been protected from the harsh realities of the adult world. However, Grimm’s fairy tales and other folktales, in their original versions, are a clear contradiction to the idea that children need to be protected. Recurring themes of dark forests, big bad wolves or hags and witches waiting for lost and vulnerable children are thought to have been told over and over to children as life lessons based on the necessity of fear in order to survive.

In roughly the last ten to fifteen years, there has been a slow expansion of harder themes introduced through picture, teen and young adult books (both fiction and non-fiction). These are themes that no longer sugar coat or deny the harsh realities that many children are grappling with in their family or personal lives. This new reality, reflected in the publishing world as well as school and public libraries, is bringing subjects close to home that make many adults uncomfortable, especially in the presence of children: death; loss; separation; gender and sexual identity; physical, cognitive or emotional abilities; emotional management; suicide; sexual assault; divorce; incarceration; substance abuse; domestic violence; war; illegal immigration; religion; homelessness; etc. The list is long.

Whether children and teens should have access to these books has recently driven political agendas further into classrooms and libraries. The American Library Association makes our professional position clear: access to information is our right as American citizens. Parents may, and should, step in and navigate what they think is best for their own children, and school teachers are now trained to work with parents to give optional reading choices. However, one person or one group of people should not have the right to make a decision for another person or group of people.

The question remains though: can children and teens digest these topics? They may have classmates who are going through very difficult experiences at home or personally. This is where the beauty of reading can come in to help individuals process information, emotions or situations. When they read books where characters are going through the same experience, books become a mirror and they realize they are not alone. When they read books about the experience of others that may not mirror their own lives, books become a window to the lives and struggles of others, giving them as readers an opportunity for learning about compassion.

Research studies have argued that children and teens actually can process tough topics, with conversation being a vital part of this process. National Public Radio’s “Life Kit” podcast gave several takeaways as to how to talk about difficult topics children and teens might see or hear about from news sources:

Murphy Library’s collection of picture, informational and teen fiction in the Alice Hagar Curriculum Collection strives to collect books that represent a wide range of experiences that children, teens and young adults may experience or will learn about from others. It may not be easy to find the appropriate subject search term, but librarians are ready to help at the Reference Assistance desk on the first floor. Engagement and Curriculum Collection Librarian Teri Holford’s office is now situated in the Curriculum Center, where anyone can find assistance to find the book they’re looking for.

A selection of books on some of these topics within Murphy Library’s Curriculum Collection can be found below.

Additional resources:

“The Proudest Blue,” written by Olympic medalist Ibtihaj Muhammad with S.K. Ali and art by Hatem Aly deals with the topic of peer pressure for wearing cultural headwear at school.

“Wednesday” by Anne Bertier discusses overcoming differences and “othering” to cooperate and creatively work together.

“The Boy Who Loved Maps,” written by Kari Allen and G. Brian Karas covers the topic of self-awareness, opening one’s world to others with different interests.

“The Library Bus,” written by Bahram Rahman and illustrated by Gabrielle Grimard covers the importance of access to education for girls in countries where it has been taken away.

“Two White Rabbits” by Jairo Buitrago and Rafael Yockteng is a story about a father and daughter who ride on top of trains to find a better life.

“Finn’s Feather” by Rchael Noble and Zoey Abbott is about finding meaning in nature’s tiniest signs as a way to find hope after the death of a loved one.

"Speechless: The complexity of wordless picture books"

A picture book without text may seem like an oxymoron. Picture books usually live up to their reputation of words and images working together in tandem to offer the reader a pleasant and agreeable reading experience. After all, picture books are the bedrock of literacy for young children because they introduce the magic of words through sounds, repetition, alliteration and new vocabulary. Students who attended this instruction session were first introduced to the library’s collection of wordless picture books with a hands-on activity of thumbing through a few selected books. After allowing their eyes to adjust to processing pages without words, they quickly realized that the experience differs from “reading” in that the art in high-quality, wordless picture books carries the story effortlessly from page to page. Nothing falls flat. Not only does the story flow, but the reader becomes engaged in new ways because reading a wordless picture book offers a different kind of participatory experience. The reader actively drives the story in their own way, with their own words and imagination, turning the experience into a lively literacy adventure and conversation.

Cover image of "What Whiskers Did," by Ruth Carroll, the first wordless picture book to be published in the United States in 1932.

Wordless picture books have been around for a long time. The first one published in the United States was Ruth Carroll’s "What Whiskers Did" (1932). While not many others were published in the decades that followed, author-artists and publishers caught on again much later when author-artist David Wiesner published a series of wordless picture books in the 1980s and 1990s. Other author-artists, whose wordless picture books can be found in Murphy Library are Arthur Geisert, Barbara Lehman, Mark Pett, Aaron Becker, and Suzy Lee.

There is more to observe in wordless picture books besides just the story. Despite the fact that students in this instruction session were learning to evaluate wordless picture books in the context of early childhood literacy, they were encouraged to look past the quality of the art and closely examine other visuals, such as how the artist uses the space on the page. Between 1932 and into the 1980s, the artwork, for the most part, took up the entire page to communicate what was happening and advance the story. Starting in the later part of the 1980s, the content on the page started to break up and fragment into bits of story separated by white space or frames, offering the readers’ eyes a new visual experience. Students were asked to ponder and possibly consider researching whether children at this early age are cognitively able to piece together a story this way (the American Academy of Pediatrics has determined that the age range of early childhood begins before birth through eight years).

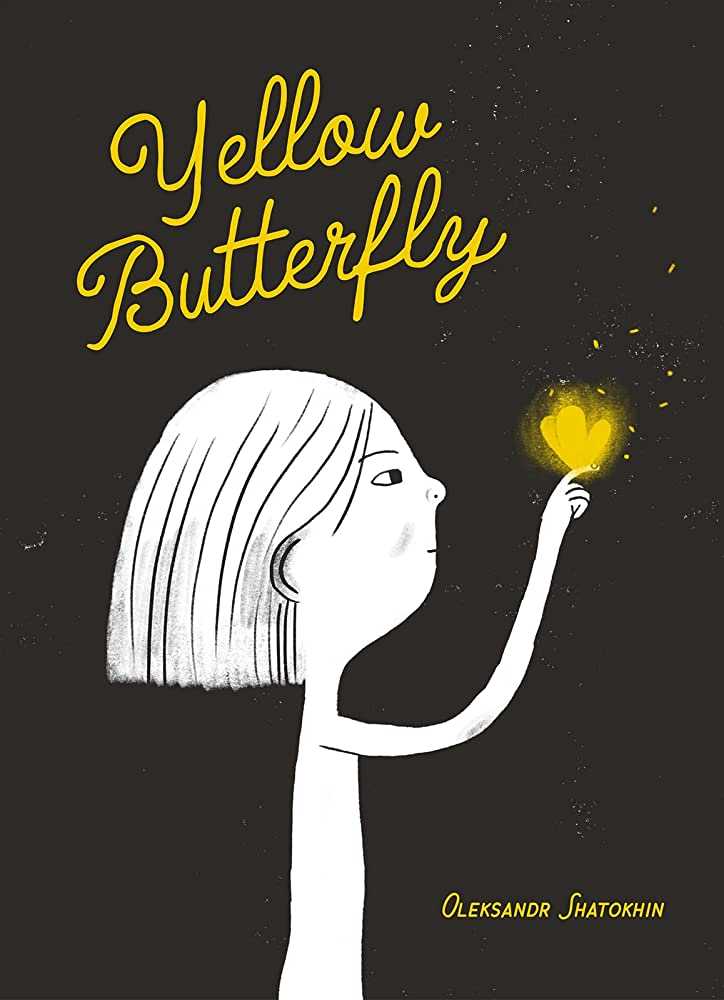

Cover image of the wordless picture book "Yellow Butterfly" by Oleksandr Shatokhin

Besides the quality of the art and the use of space on a page, another aspect of evaluating wordless picture books is to examine the content itself. More recent wordless picture books are now bringing stories and experiences that may need an extra layer of consideration, especially for the early childhood age range. In Ukrainian author-artist Oleksandr Shatokhin’s "Yellow Butterfly, A Story From Ukraine," published in 2023, the story of a girl experiencing war is defly expressed using a monochromatic palette of black, white and gray, along with carefully added touches of yellow butterflies that sometimes distract the girl from her war-torn world to lift her up and carry her away to past happy memories. Shatokhin’s art expresses alliteration similar to words: repetition, patterns and scale portray a girl’s emotions as she tries to process the daily realities of war.

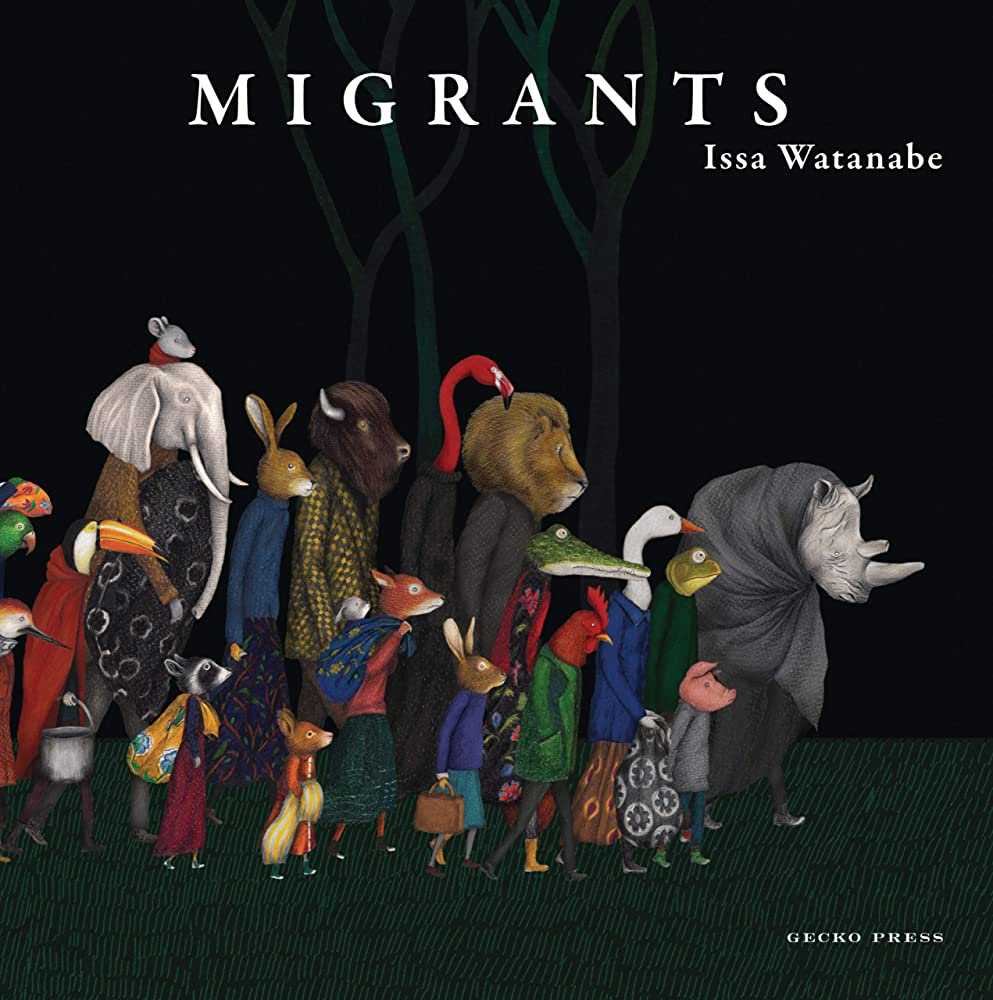

Cover image of the wordless picture book "Migrants" by Issa Watanabe

In another book, Peruvian author-artist Issa Watanabe’s "Migrants," published in 2020, takes an honest and hard look at migrants. Her colors are stark against solid black pages. A mixed group of animal migrants on the run is followed closely by the figure of death as a skeleton traveling with an ibis. As the group moves across the pages toward a place yet to be defined, they endure many hardships. Not all make it through the forest, to the river, on the boat. Death is never far behind. This book is unapologetic in its portrayal of displaced groups searching for a better life.

One last observation that students of this instruction session learned firsthand is that wordless picture books can reverse roles. No longer is the story coming uniquely from the adult reading the text. The child participates, interprets and propels the story with their own words and ideas. And there is nothing wrong with shaking things up a bit.

Collective biographies in children’s and teen books

For years, picture books and informational books have been easy to visually distinguish. Picture books are rooted in art and images along with the author’s text, and the two work together to make an aesthetically pleasing experience. Informational books, also called nonfiction books, have traditionally given more attention to the text on the page, made up of facts, events or other information regarding science, history, social science or biographies of famous people. Visual images thus play a secondary role. The distinction between these two styles of books has driven how library spaces are organized, with picture books in one section arranged by the author’s last name and nonfiction books located elsewhere and arranged by subject according to the Dewey Decimal System.

However, publishing trends in children’s books have seen a recent blending of these two types of formats, which has muddied the distinction. Picture books are now drawing from and including more informational content, and nonfiction books visually look more like picture books, with more artistically interpreted content being given increased space on the page. One can no longer count on quick visuals to understand the differences.

Biographies for children, for example, have usually featured one single person. Some figures have had several biographies about them published in a single publishing season: Ada Lovelace, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., Georgia O’Keefe, or Frida Kahlo. A running joke among children’s literature professionals is whether the world really needs yet another biography of Frida Kahlo! Whether one agrees or not, biographies spark an interest from young readers. This type of content encourages them to try and put themselves in the shoes of a historically remarkable person as well as teaches the importance of new perspectives in understanding their own life. Readers of biographies learn about someone else’s experiences, see their own world in a new way, learn what it was like to live in that period, and acquire valuable life lessons.

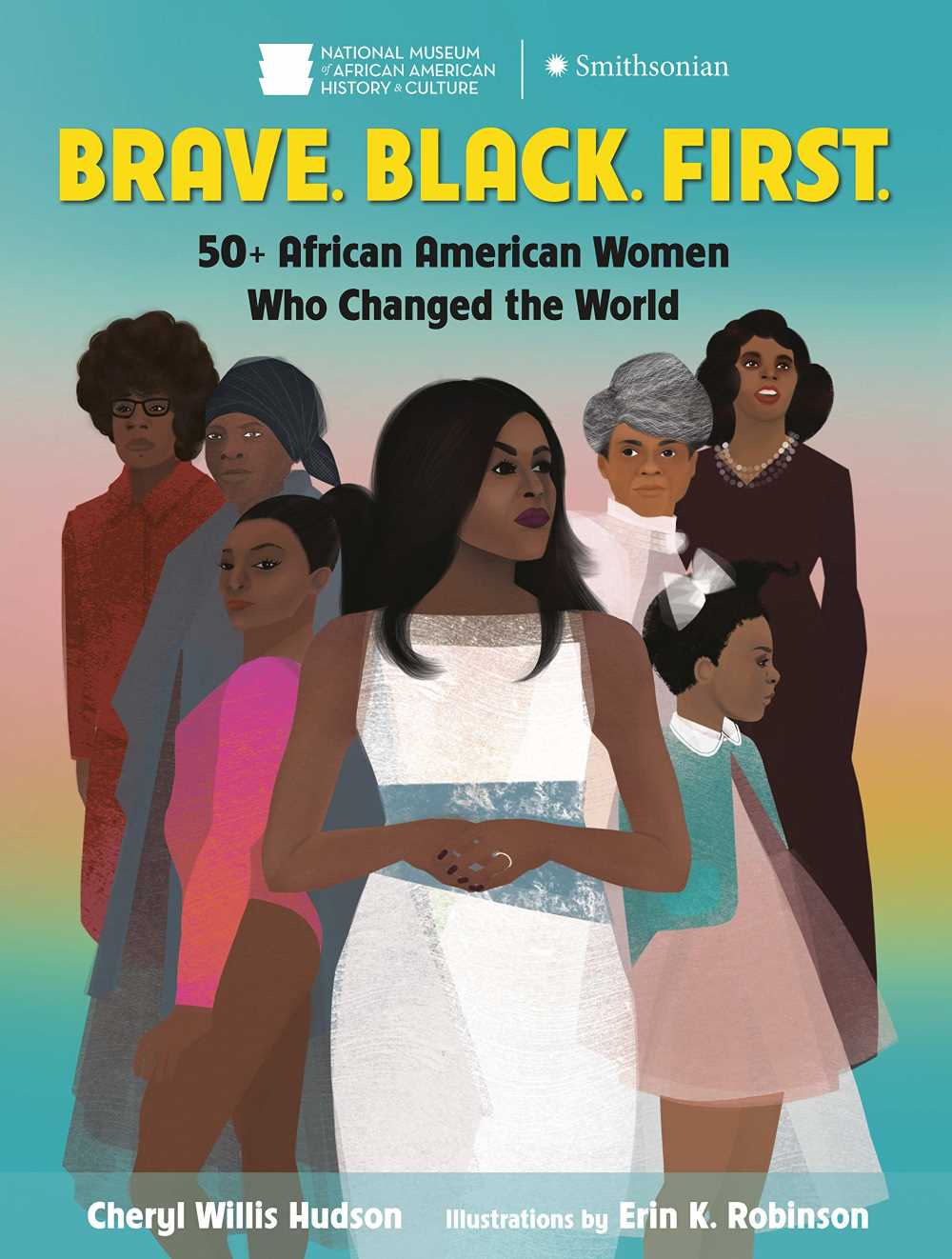

In the past few years, we’ve seen more “collective biographies” in children’s publishing. Instead of concentrating on one single person, the author compiles several people with a common experience but not necessarily from the same time period. These collective biographies often merge the traditional picture book and informational book formats to deliver biographical information in a visually artistic and engaging way. While posing a potential challenge to the organizational structure of a library, presenting information on performers, politicians, athletes, scientists or artists in this way means a collective biography offers even more exposure to the priceless experience of learning about someone else’s challenges and how they overcame them.

One popular topic within this genre is women throughout history. Check out a few examples of collective biographies on this topic from Murphy Library’s Curriculum Center below:

Math Inaccuracies in Picture Books

"I need a picture book on shapes with flawed information."

Certain user requests are simply perennial in nature. Once a semester, math education students flock to Murphy Library’s Curriculum Center in need of a “picture book on shapes with flawed information”. Invariably, the librarian is stumped. Flawed information, not being a very decisive criteria in collection development, makes for a tough request to fill. After a few seconds of the deer-in-the-headlights look, said librarian might ask, “what kind of flawed information?” This is when the student becomes stumped. It becomes a ping-pong exchange of trying to explain and understand what “flawed information” might look like in picture books on shapes.

As it turns out, of the increasing amount of published children’s books intended to teach shapes available on the market, very few of them are devoid of flaws. Most of them are misleading, confusing, and surprisingly inaccurate when it comes to providing mathematically accurate information on shapes. Research shows that when fundamental concepts are not taught or introduced correctly to children in early childhood, their understanding is resistant to change in later years when, as high school students, they are formally introduced to geometry.

Do a quick search in your libraries (shapes--juvenile fiction), pull the books, and start to analyze them with critical eyes. Ask yourself these questions:

How many shapes are featured? (Concept books usually only feature the most common four: circle, triangle, square, rectangle, which limits a child’s exposure to other mathematical shapes).

What orientation are the shapes shown on the page? (most concepts books only show shapes in a horizontal orientation, limiting a child’s recognition of shapes in other contexts when the shape is not horizontally orientated).

Is 2D language being confused with 3D objects? (Circles are not balls. Balls are circular. Doors are not rectangles. They are rectangular. Musical triangles are not triangles, because their corners are rounded and one side is open).

How are the shapes introduced? (Most concept books do not introduce shapes using mathematical properties, therefore children do not learn to define, say, a square, and are confused when they must learn later that a square is actually a rectangle. Research shows that children can deal with abstractions).

Does the book include all kinds of non-mathematical “shapes” like stars, diamonds, ovals or hearts? (If the book intends to set the stage for geometrical shapes, it’s helpful to separate mathematical shapes and “other” shapes. Clarifications like this can be great teaching opportunities during story time).

Are the shapes just acting like characters in a story? (If the shape characters can be replaced by animals or people without changing the story, it probably isn’t a book intended to teach shapes).

If so, bingo! You’ve got a few books with flaws that will do quite nicely for this assignment.

There is also a box of picture books on shapes on Reserves at the Circulation Help Desk.